Make sure to also listen to our one-hour discussion of the Pathfinder Second Edition Rulebook on the Roll For Combat podcast. Also, make sure to read Jason’s review of the Pathfinder Bestiary.

If you enjoyed this review make sure to check out our brand new Pathfinder Adventure: The Fall of Plaguestone Actual Play Podcast!

It feels like it’s been on our radar for a while, but with a formal release scheduled for GenCon 2019, Pathfinder Second Edition is finally being released into the RPG wilderness. Our secret operatives have managed to get our hands on the new Core Rulebook and wanted to share our first impressions on the next chapter in Pathfinder gaming.

If you think about it, Pathfinder First Edition is a decade old and was itself a revision of an existing system (Dungeons and Dragons 3.5), so there are a lot of miles on that odometer. The flip side of 15 years of depth, is 15 years of kludges, conflicts, workarounds, and other annoyances. New Class X is better than Class Y in every way, so much so that no one bothers playing Class Y anymore. Something written in sourcebook A directly conflicts with thing written five years ago in sourcebook B but nobody caught it until it was already in print. A new book comes up with a better mechanic for something that really should’ve been The Way It Was Done all along. Game design as a discipline is more of a formal thing now; we simply understand the inner workings of these games better than we did 15 years ago.

The other elephant in the room that we long-time players have to acknowledge is that we’re at a time when new players are kicking the tires on this hobby, and 15 years of complexity equals 15 years of “holy crap, this is complicated!” when a new player sits down at the table for the first time. Those of us who have been playing all these years may live and breathe and even love that complexity, but at a time when roleplaying games are receiving newfound mainstream acceptance (thanks, Stranger Things!) and people who never threw dice before are giving this hobby a fresh look, rolling a forklift stacked with books up to their doorstep is a bit daunting.

So you can see the needle Paizo has to thread here. Second Edition needs to preserve what was best about First Edition, and deliver something that still feels like the Pathfinder we know and love. It also needs to take advantage of everything they’ve learned about their product over the last 15 years and condense it down to a new “best” version of the game. And while they’re doing all of that, make it simpler and more accessible to new players without making us lifers feel like it’s been dumbed down past the point of recognition.

Oh, is that all?

After sitting down with these rules for a while, I feel like they did a pretty good job of hitting the mark. While it’s still recognizable as Pathfinder, it does some things differently in ways that will hopefully make for more interesting gaming. I’m not going to pretend it’s perfect – there are some things I not that crazy about and would want to see in a live game before I make a final decision. But all in all, it’s a good first step and our gaming group is definitely going to give it a look. I’m going to roughly follow the structure of the book since that seems like a logical way to tackle this.

Getting To Know You (Ancestries and Backgrounds)

The first few chapters deal with character creation, for which Paizo has helpfully supplied us with a mnemonic of “ABC” – Ancestry, Background, Class. If you’ve been following Starfinder at all, it’s very similar to the character creation in Starfinder: you choose these three aspects of your character, and those choices do a lot of the heavy lifting in terms of shaping your ability scores, hit points, languages, and so on.

Ancestry is what we longtime players have heretofore been calling race, but “RBC” doesn’t really work. All of your usual fantasy roleplaying classics are here – elf, dwarf, halfling, etc. – with a few minor caveats. First, half-elf and half-orc are no longer considered separate entities but are considered variants (“heritage” is the official terminology) of humans. Second, Paizo’s official mascot – the goblin – is now one of the base playable ancestries. Me, I’m not a goblin guy (sorry… please, no hate mail), but I know a lot of people love the little guys.

Under the umbrella of ancestry, additional flavor is available through the selection of a “heritage” (say, the difference between a wood elf and high elf; half-elf and half-orc are technically human heritages), and ancestry feats. Ancestry feats are talents you can take to customize even further – you might take Nimble Elf and take an extra five feet of movement speed; I might take “Otherworldly Magic” and take a cantrip I can cast whether I’m a caster or not. Furthermore, you get additional ancestry feats as you level, so the customization grows over time. So your elf and mine already have subtle differences before we even get into classes.

Background is a one-time, static choice – what was your character doing before they became an adventurer? Nuts and bolts, background gives you a few ability increases, a Lore skill (like Knowledge skills from Pathfinder 1, but can literally be ANYTHING), and another skill. At a roleplaying level, it can help shape the story of your character. Were you a noble? A prisoner? A merchant? There are a lot of choices, so roleplayers and min-maxer types should be able to find something that makes their character work.

A Touch of Class (Classes)

Of course, class is the meat and potatoes of character creation. As with ancestry, all your old RPG favorites are here (joined by Alchemist as a core class). But within the familiar, there are wrinkles. The bard is no longer a hobo caster and has been upgraded to a full caster class with a full spell list. A sorcerer can choose a bloodline associated with any of the four magical sources – primal, arcane, divine, and occult – so yes, you can have a sorcerer that heals. The position that used to be occupied by the Paladin is now the Champion – the Paladin still exists as the lawful good variant, but Neutral Good and Chaotic Good champions can also exist.

One thing that’s neat is that each class has multiple different specializations available from a fairly early level. With some classes, the choice can be more of a subtle flavor; others look like they could play dramatically differently. For example, if you’re playing an Alchemist, you can play a Bomber (‘splodey direct-damage), a Mutagenist (buffs for yourself, debuffs for enemies), or a Chirurgeon (healing). Champion feels like a class where it’s more flavor – they all play as divine-inspired fighters, but some of their supporting powers are tweaked based on the variant – the lawful paladin gets more powerful when getting revenge for damage already done, the neutral redeemer applies debuffs to enemies (YOU SHOULD BE ASHAMED OF YOURSELVES!), and the chaotic liberator’s powers focus on freedom of movement and action.

One thing that’s very noticeable across all classes is the “feat-ification” of class abilities. In First Edition, a lot of core class abilities were static – every character of a particular class gets the same tools at the same levels. In Second Edition, there’s still some of that, but a much larger portion of class abilities are distributed in the form of class feats, and you have multiple choices available at any given level. To take one example, a second-level cleric can choose (among other things) Turn Undead, Communal Heal, or grab additional cantrips with Cantrip Expansion. It’s going to take running some characters up to higher levels, but it feels like this could lead to interesting character choices, where your Level 10 ranger and my Level 10 ranger could end up playing a LOT different from each other.

Feats Don’t Fail Me Now (Feats)

I’m actually going to go out of order in the book and stay with feats for a bit. (Skipping over the chapter on Skills, but we’ll come back). One thing you might have picked up on by now is that Second Edition puts feats in silos quite a bit. In First Edition, pretty much everything was just a feat – as long as you meet the prereqs, you could take anything you liked. Wizard with heavy armor and Cleave? Have at it, if you can make it work. Now, we have Ancestry Feats, Class Feats, Skill Feats (we haven’t discussed them yet, but they exist), and they’re all on separate tracks. There are a few general feats anyone can take, but it’s a much smaller number than before.

I will acknowledge that this might be a mixed bag to some players. The downside is that people who are into creating really niche character concepts might struggle to do that with all the tools walled off in different places. If you just want to steal one or two abilities, there are ways to do that – most notably, there are multiclass feats that let you grab something from another class. But there are probably going to be some builds from PF1 that just aren’t going to be possible in Second Edition.

If there’s an upside, it’s that they’ve basically eliminated the so-called “feat tax”. In PF1, you could tie up three or four feat slots laying the groundwork to get the destination feat you really want. In PF2, character level is the single biggest gatekeeper to taking a feat: if you’re high enough level to take the feat, you’re good to go. The difference is not so much the destination feat itself – in both systems, you might not be able to take the feat you really want until level 12 – but what you’re doing in the meantime. In PF2, you’re taking other feats that make your character more interesting whereas, in PF1, you often ended up checking boxes instead of taking the things you really wanted. (On the other hand, I know there are going to be a few players who are gonna be pissed because they had a meticulously crafted build that got them that feat by Level 9 and think it’s arbitrary they have to wait for Level 12 now.)

The one sort-of exception is skill feats, where you need to have a specific character level, and in some cases, need to be trained to a certain level in a skill. There are some surprisingly useful things hidden in the skill feats. Treat Wounds is a heal you can get through the Medicine skill that doesn’t require magic. Trick Magic Item gives you a chance to use a magic item even if it’s not normally something you could use. There’s also Recognize Spell, which lets you identify a spell as a reaction as it’s being cast.

The real intriguing ones are the high-level Legendary skill feats. They don’t kick in until you reach Level 15 and achieve Legendary in a particular skill, but… whoo, boy. Legendary Linguist in the Society skill lets you come up with a pidgin language in real-time. For ANY language. Legendary Sneak, in Stealth, literally gives you a chance to hide in plain sight. But the best has to be Scare To Death, for the Intimidation skill. As the title says, you have a chance to scare an enemy so bad it just up and dies.

A View To A Skill (Skills)

Technically, we’re now going back a chapter, but let’s talk about skills. I’m not going to spend a lot of time about the skills themselves – they’re mostly the same ones that have been around since First Edition and even before: OK, what used to be called “Knowledge” is now “Lore”, Climb and Swim are now lumped under “Athletics”, and “Handle Animal” is now a specific action you can take under “Nature”, but the broad strokes won’t be surprising to anyone. I should mention that Lore is more open-ended than Knowledge was – Knowledge had specific categories; Lore can literally be anything. (OK, not motorcycles, because they haven’t been invented yet. But you know what I mean.)

I wanted to spend my time talking about some of the surrounding logistics of the skill system.

First, the math associated with skills has gotten a whole simpler. The days where you put ranks into skills every level are gone. Now skills only have five levels (or, four plus “untrained”) – Trained, Expert, Master, and Legendary – and the bonuses associated with those levels are simply +2, +4, +6, and +8 respectively. You also get your character level IF you’re trained in the skill, but not if it’s untrained. Additionally, instead of getting a certain number of skill ranks every level, you just get skill advancements at certain points during character leveling.

This is one of those areas that at first, I thought it was TOO simple, but then I thought about it, and this may actually work out better in the long run.

First, it represents the difference between choice in name only, versus engaging, interesting choice. In First Edition Pathfinder (or Starfinder for that matter), it was feast or famine – you were either a low-skill character who only got enough skill points to put points in a few core skills and nothing else; or you were a skill monkey and had so many choices it became silly once you put a few points in INT. I just leveled Tuttle in our Starfinder game, and he gets something like 10 or 12 skill choices per level and… if I’m being honest, choosing his skills isn’t that interesting. “Here are the seven skills I take every level, here is the cluster of skills where I round-robin between them, and then I have one or two points to be stupid and bump up against things I’m never going to be good at anyway”. It’s choice in name only.

Second, the math is a little flatter. The highest skill bonus you can get is 8 plus your ability score modifier, so there’s no more “I roll a +32 for 44”. With the math being flatter, the GM doesn’t have to ratchet up skill challenges to stay ahead of the players who can roll highest, which means the lower-skill players don’t get left as far behind. You’re still out of luck if you’re TOTALLY untrained in a skill, but maybe that’s as it should be.

The other thing that’s new and neat is that there’s now a formal means of using skills to make money during downtime. It was always supposed one could make money with a skill, but mostly left to the imagination. Pathfinder 2 formalizes it. Officially, it’s most commonly associated with Craft, Lore, or Perform, but if you and your GM can come up with a job you could perform to earn money with another skill (e.g. use Nature to work as a stable-hand), it’s within the GM’s discretion to allow it. You work with the GM to determine what jobs are available, the GM sets a DC for the work you’re doing, and you roll to see how well you do the work. You still get paid SOMETHING even if you fail your check, but passing the check and being more proficient in the skill let you earn more.

One more thing I feel is worth mentioning is that the concept of “Take 10” and “Take 20” – saying “we’re going to do XYZ until it works” – is basically gone. On one hand, Take 10/20 was sometimes a really convenient short-hand and moved action along, but it was arguably prone to abuse and sometimes broke the immersion of storytelling – yes, there’s a creature on the other side of the next door, but he’s going to ignore us while we search for twenty minutes.

The main reason it has to go away is because of critical successes and critical failures, which now apply to many skill checks. This is a little bit oversimplified, but a natural 20 or making a skill roll by 10 or greater is a critical success and a natural 1 or missing by 10 or more is a critical failure. Since there’s always a possibility of a negative outcome, the system can’t really accommodate the Take 10/20 like it used to. Having said that, it can still exist in the GM’s mind – if there’s enough time to perform a skill in a leisurely fashion, he or she can give a bonus to the roll that accomplishes most of the same thing.

Don’t Forget Your Spare Underwear (Equipment)

As with skills, I’m not going to spend a lot of time on the charts of equipment themselves. You don’t need to read 300 characters on the fact that yes, “50 feet of rope” is still a thing. I’ll more talk about the systems that exist around equipment, and particularly those that have changed from First Edition.

One of the biggest shifts is a small one, but I’ll mention it – the silver piece has basically replaced the gold piece as (pun semi-intended) the coin of the realm. Things don’t really cost any more – starter gear, in particular, is the same once you move the decimal. But it does mean that find a few gold pieces is more of a big deal than it was before.

Let’s also talk about encumbrance. If you’ve been following Starfinder, Pathfinder 2 makes use of the “Bulk” system from that game. There’s no more “I’m carrying 230gp of weight”. Most items have a bulk value – either a number, L (for “light”, with 10 light items counting as 1 bulk) or some items are light enough to have no bulk. Your carrying capacity is really simple: 5 + (strength modifier) to be encumbered; 10 + (strength modifier) and you can’t carry anymore.

I will discuss ONE specific class of item here: shields. In Second Edition, shields go from a passive bonus to an active defense system. It used to be that if a shield was equipped you got the bonus to your AC automatically. Your abstract tin can gets a little stronger. Now you have to actually raise your shield to get the bonus; however, if you do, not only do you get the AC bonus, but even if you get hit, the shield can take the damage. Up to a point… shields do have hardness and enough damage will eventually break a shield. I have to admit this part worries me a little – at one point we were joking about fighters having to carry a wagon of extra shields through dungeons with them. It’ll be interesting to see how often shields actually break and need to be replaced “in the wild”.

There’s also a revamped crafting system, but I don’t think a lot of people are going to be crafting off-the-rack stuff so we’ll come back to that when we reach the part of the book that deals with magic items.

Watch Me Pull A Rabbit Out Of My Hat (Spells)

Again, I’m not going to spend time on individual spells for the most part. I’d rather talk about the ways magic has changed in Second Edition. I feel like “flexibility” is the theme here; casters can now get more out of spells and use them in more interesting ways.

One example is scalable cantrips. In prior editions, low-level casters would eventually reach a point where they’d run out of “good” spells and would be left with either cantrips that didn’t scale (that Level 8 creature laughs at your 1d3 Ray of Frost) or abandoning their core skills and using melee or ranged weapons. With Second Edition, cantrips scale, so a caster always has SOMETHING he or she can do. A cantrip’s never going to be your BEST spell, but it’ll at least keep you in the fight.

Another nice change is the concept of heightening. A lot of spells – particularly, but not exclusively direct-damage spells – can be more powerful by putting them in a higher spell slot. Note that this can be either +N levels, or a spell might have specific tiers (2nd, 5th, 8th). Let’s look at healing, for example, there’s no more Cure Light, Cure Moderate, Cure Serious where you have to learn each one. Now you have “Heal” and it’s 1d8 per level of the spell slot you put it in. I’ve oversimplified this a LITTLE – there are some circumstances where a caster would have to learn both the regular and heightened version of the spell – but for the moment, know that it’s there and it can be a pretty powerful tool for expanding a caster’s arsenal.

Heal also demonstrates another way in which magic can be more flexible through the use of actions. Some spells can have different effects depending on how many actions you spend on them. With one action, Heal is single-target and has a range of touch. With two actions, it’s a ranged single-target heal. With three actions, it becomes an area-effect channel. For another example: Magic Missile – more actions simply means more projectiles.

My hope is that this will actually lead to more interesting caster characters because the flexibility will free up spell slots for other things. Now, you don’t have to spend half your spell slots just to keep your best damage or healing spells current; that should leave players with more spell slots for utility choices.

There are two other small things I wanted to mention. Burying the lede a little, we also have Level 10 spells! Now, there aren’t a LOT of Level 10 spells – only four or five per magical source. That’s partly because they’re really powerful, but partly because heightening reduces the need somewhat: some of your Level 10 spells are just going to be heightened lower-level spells. But there are some cool things here. Each source gets a catch-all that amounts to “any lower-level spell, whether you know it or not”. Arcane casters can stop time. Primal casters can turn themselves into a kaiju or turn their party-mates into a herd of mammoths. Divine casters can turn themselves into an avatar of their god or raise the dead. Like I said… cool stuff.

The last thing I wanted to mention is focus spells and rituals.

Focus spells are the way non-casters like Monks and Champions get their powers, but they’re also available to regular casters through feats, for which they’re almost like a cantrip on steroids. It’s a spell that can be cast with a separate set of points (focus points) instead of spell slots, and you can get back at least one point by taking a 10-minute rest. So it’s another way to get a scalable (it always casts at half your level) repeatable spell without using spell slots.

Rituals are spells that are powered by skills rather than magical power (and also have a cost in material components). Rituals are non-combat activities, lasting hours or days, but the requirement to perform a ritual is usually a primary skill and one or more secondary skills. Magic is not strictly required, though, for a lot of rituals, the primary skill might require ranks in one of the magical arts. To give an example: a Resurrect ritual requires Expert-level Religion as the primary skill, with Society and Medicine as the secondary skills. So a group of fighters who happened to have the right skills could perform a resurrect ritual, but a Cleric is far more likely to have Religion trained to the right level.

Golarion For Dummies (The Age of Lost Omens)

This is the base-level world-building chapter – it introduces you to the places, factions, gods, etc. Not that this stuff isn’t interesting, but a) except for deity restrictions for divine-flavored characters, it doesn’t really impact gameplay, and b) spoiler alert – there’s also going to be a whole sourcebook on this stuff (The Lost Omens World Guide), so I’ll spend my review energy there. Moving on.

Everyone Was D20 Fighting (Playing The Game)

This chapter is mostly, but not entirely, How Combat Works.

Let’s start with the single biggest and possibly most polarizing change. One thing that immediately leaps out what Paizo has done with the action economy. In First Edition, you had a Batman Rogue’s Gallery of actions – full-round, standard, move, swift, free, Clayface – and figuring out the basics of what you could do each round got a little convoluted. Now, pretty much everything is just an action, and you get three of them. (I say “pretty much” because Reactions are still a thing and the free action still exists for REALLY simple interactions, but everything else is an action.)

Now, I know that sounds overly simplistic at first glance. I’ll go ahead and concede the point because that’s how I felt when I first heard it. But here’s the dirty little secret. They didn’t really lose the complexity, they just moved it to the other side of the equation. Everything’s an action, and you get three of them, but some spells and attacks can have different effects depending on how many actions you put into them. As I mentioned in the chapter on spells, a spell can do different things based on how many actions you pump into it. Yes, you can take three attacks, but you get a -5 to hit for each extra attack you make (or -4 with finesse weapons), so there’s some cost-benefit there. Raising your shield is an action, so if you want to get that extra attack in, you lose the AC bonus from your shield. You still have interesting choices, you just lose the sometimes-tedious terminology. Where the rubber meets the road, I’ll say that 90% of the time, it’s a wash and the other 10% of the time feels like you’re making tactical choices that matter rather than figuring out how tightly you can pack a suitcase.

Another thing that could be a bit of a game-changer is that the Attack of Opportunity seems like it’s going to be a lot less of a dominating force. In First Edition, EVERYONE could do attacks of opportunity and combat generally devolved into a dance of five-foot steps because nobody wants to eat an attack of opportunity. In Second Edition, Attack of Opportunity is a specific skill, and not everyone has it. On the player side, fighters get it automatically as a class skill at creation, a couple of the other melees can take it as a class feat (Level 6 seems common), but other classes would have to get really creative with multi-class feats to get there. I haven’t had a chance to inspect the monster lists in great detail, but anecdotally, it seems like the same goes for enemies too – there might be a few enemies who have the ability, but it won’t be universal. I feel like this could open up the battlefield in interesting ways and make combat a little less “line up and take swings until someone drops”.

I mentioned it in the skills chapter, but I’ll bring it back again here – the role of critical successes and critical failures has expanded. Now the definition of a critical success is exceeding a DC by 10 or more, and a critical fail is defined by failing by 10 or more, and a natural 20 or natural 1 just adjusts the degree of success up or down one level.

It may seem like it’s a small semantic difference, but it does have some implications for combat. First, it puts a lid on crit-farming because if a natural 20 would be a miss, it doesn’t generate an automatic crit anymore, it just generates a regular hit. Similarly, it should better capture the flavor of (to use a wrestling term) “squash matches” where one side is way overpowered. Now, the more powerful side will get a lot more crits and end the fight more quickly. Fun if you’re the Level 10 party fighting Level 1 kobolds and can crit on a 13 or 14. Not so fun if the party runs across an adult dragon and they’re the ones getting critted over and over.

Hero Points also become a formal thing in Second Edition. I know this was already pretty popular as a house rule – if you roleplay well or come up with something clever, you get a re-roll in the bank for when you need it – but Pathfinder Second Edition formalizes it. Now you get one Hero Point at the beginning of each session and can earn more through interesting play choices (but can only hold 3 at a time). As far as spending them, you can spend one point to re-roll (but you HAVE to use the new roll), or you can spend all your points to stabilize from dying. Moral of the story: ALWAYS keep a spare Hero Point around, just in case.

Shall We Play A Game? (Game Mastering)

This is another chapter I have to admit I glossed over a little because it’s mostly information for novice GMs sitting down at a table for the first time. There are a few useful nuggets in here, including a lot of sample hazards (aka traps), but most of it is 30,000-foot “how do I start a game” information. The trap stuff is kind of cool – traps get increasingly difficult to both spot and deactivate, so only trained people can even do it, and some traps even require multiple steps to deactivate safely.

Medieval Q-Branch (Crafting & Treasure)

I feel like this is a chapter that’s going to be one of the most polarizing ones. Basically what we’ve got here is all your old favorite magic items (yay!) along with a bunch of restrictions about how you can use them (boo!). GMs who saw the weak spots in the system and know magic items had the potential to break the game will probably either outright like these, or AT LEAST understand the necessity of them. Players will mostly be annoyed at the new levels of inconvenience; it’s really just a question of how much.

Take the concept of investing. Most magic items other than consumables need to be “invested” once per day – think of it as bonding with the character. Weapons and armor are in the middle – if you don’t invest, you still get the pluses, but you lose any special abilities. However, you can only invest 10 items per day, and if you take one off, it loses its investment and you have to do it again to re-use it. GMs will see it on a check on players bringing the perfect magic item for EVERY situation; players might see it as a hoop to jump through.

Similarly wands. Wands don’t have to be invested, but you can only use the wand once per day. You can use it a second time (and the spell will go through), but you have to roll a DC10 “flat check” (i.e. no modifiers, just the die roll), where failure overloads the wand and it’s destroyed. I get why wands had to be checked a little – our group was notorious for buying Cure Moderate Wounds wands in bulk at the Golarion equivalent of Costco (Who is this powerful mage, “Kirkland”?) to the point where out-of-combat healing became trivial, so… I GET it intellectually, but I can’t say I’m thrilled by the idea.

On the other hand, they’ve also added a new consumable class of magic item: the talisman. Talismans are cheaper, one-shot magic items that can be affixed to weapons or armor but disintegrate after use. And they can be affixed to a piece of gear with a single action, so it would appear you can add a talisman in combat. Scrolls for fighters, sorta? A fairly straightforward example of this is a Potency Crystal, which makes your weapon a magical weapon, but only for one turn. The single-use makes them kind of underwhelming, but they’re flexible and also fairly cheap, which might play well with the new crafting system.

Told you I’d come back to it.

Crafting is a little more of a process in Second Edition than First. You don’t just roll out of bed and say “I’m making Baba Yaga’s Hut today”. First, you have a recipe, and recipes for rare items are just that… rare. They won’t be available in every hardware store in Golarion; they might be treasure prizes on par with wizards’ spellbooks. If you’re a crafter, your other option would be to figure out how to make one through reverse-engineering. Yes, you have to disassemble a perfectly-good magic item in working order, hope you learn how to make it, at which point you could then reassemble it. Except if you fail, you don’t learn the recipe AND you might lose some of the materials in the process. There are higher-level skill feats that help with some of this, but it’s still a non-trivial thing. So making magic items is going to be harder to do, but more of an event when you do succeed.

Weapons and armor are interesting because magical enhancements now operate on an almost MMO-ish system of runes. There are “fundamental runes” and “property runes”. Fundamental runes include the potency rune, which represents the plus, and either a striking rune for weapons which grants extra damage dice or a resiliency rune for armor that grants bonuses to saving throws). Property runes are things like adding typed damage to weapons or adding charges of invisibility to a piece of armor. You can only have one of each fundamental rune; the number of property runes is determined by the potency rune (aka you can have as many properties as pluses).

The neat thing is the runes can be upgraded or transferred, which… I don’t know how people feel about it as a game mechanic, but as a storytelling thing, I like a lot. One of fantasy’s great tropes is of named weapons (particularly swords) that go through their wielder’s journey with them, and this rune system makes that a more viable path. Gandalf didn’t sell Glamdring to a vendor because he found a better sword in the next dungeon.

I’d also note just in passing that the highest “plus” I see on a magic item is +3… the days of +4 and +5 weapons seem to be gone. Then again, if you can get a +3 AND additional damage die, maybe that’s better overall. I feel like weapons and armor will be versatile enough we won’t miss the pluses all that much.

In Conclusion

Well, that’s a wrap on this first look at the Pathfinder Second Edition Core Rulebook. I recognize everyone wants something different from their gaming table, so I’m not going to get too carried away telling you whether you “should” or “shouldn’t” make the switch. I know some people have a lot of time invested in their number-crunchy First Edition games, and if that’s what floats your boat… cool.

Having said that, I’ll give you a quick “here’s where I stand” to sum things up.

Here’s what excites me about Second Edition:

- Magic seems far more flexible and casters are probably going to be more fun to play. Yes, a lot of that centers on damage and being more effective at blowing stuff up, but I feel like it’s going to free up spell slots to use on utility spells as well, so casters will be more dynamic in general. But also… blowing stuff up.

- So far I’ve really liked the three-action economy. We haven’t played a LOT of Second Edition yet, but it feels like it adds interesting choices to the game, and it’s a lot easier to remember.

- Maybe it’s because I’m familiar with it from Starfinder, but I like the ABC character creation system. It’s flexible while being fairly simple, while still helping to define the “story” of your character. I actually think that’s pretty neat.

- I like the fact that two people can create two different characters that might be the same race and class but might play remarkably differently. I appreciate a system that can accommodate different playstyles like that.

- It’s a small thing, but bringing some structure to downtime by being able to work at a skill is a welcome change. Right now, downtime just amounts to milling about aimlessly.

Things that… I won’t say I “hate”, but the jury’s still out:

- The rules on magic items. I get why they need to exist – I’ve seen and sometimes been guilty of the excesses they were attempting to curb – but they still might end up being a little heavy-handed. It’s discouraging to get a shiny new toy and not be able to use it. It’s the one piece that overtly reeks of micromanagement.

- It’s a small thing, but shields being an active defense is a mixed bag. It adds a tactical element, but it’s also easy to forget to do, and the issue of shields breaking is something that needs data from the field. If you lose a shield every 3-4 sessions, whatever; if you lose one every other fight, that could get tedious.

- Is the feat-ification going to be TOO silo’ed? This will probably affect my group-mates more than it will affect me (I tend to play fairly simple character concepts), but I do wonder what’s going to happen when someone wants to create a really customized build that was possible under First Edition but is impossible in the new system.

- Talismans aren’t really doing it for me at first glance. I don’t know that it’s a bad idea – I just don’t like consumables in general (beyond healing potions) and another class of consumable is kinda shrug-worthy to me.

What I will say is it feels like they preserved most of what was appealing about the Pathfinder experience, while still performing some cleanup and making it more inviting to new players in the process. If a gaming system like that sounds appealing to you, Pathfinder Second Edition is probably worth checking out.

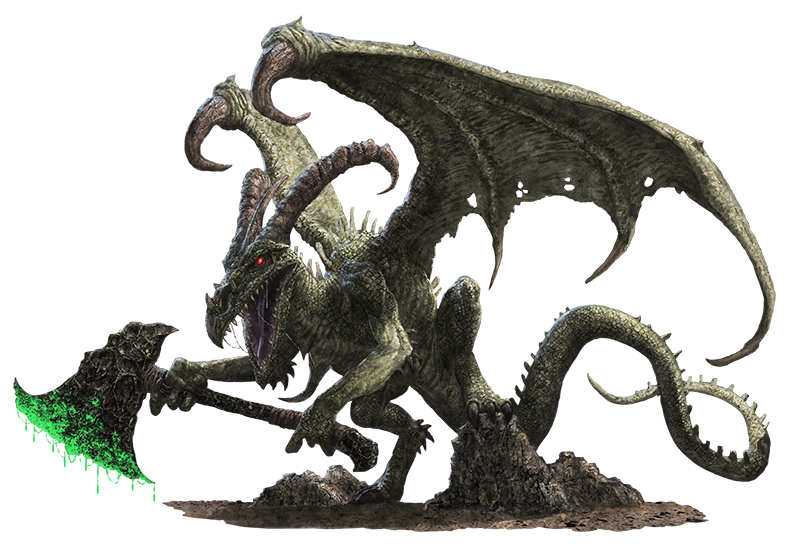

The multi-page monsters break the mold a bit to allow for additional details and more complex systems. As an example of a multi-pager (four pages in this case), let’s look at the Ravener. It’s oversimplifying it to say “what if a dragon decided it wanted to be a lich?”, but it’s not that far off the mark either. It’s basically a dragon that undergoes a ritual to become undead rather than embracing its death, and it’s as nasty as it sounds. Among other things, when it kills someone, it has a chance to eat their soul to heal itself; if it succeeds, that person can’t be reanimated by anything less than a Wish or Miracle spell while the ravener remains “alive”. The Ravener also comes with a statblock for a sample version, a process for creating your own from an existing dragon, as well as the details for the ritual it takes to create one. Oh, and if a Ravener doesn’t consume enough souls, it “starves” and becomes a Ravener Husk – more of a mindless feral version of its former self — and there’s a statblock for that creature too. Needless to say, they couldn’t fit all of that on a single page.

The multi-page monsters break the mold a bit to allow for additional details and more complex systems. As an example of a multi-pager (four pages in this case), let’s look at the Ravener. It’s oversimplifying it to say “what if a dragon decided it wanted to be a lich?”, but it’s not that far off the mark either. It’s basically a dragon that undergoes a ritual to become undead rather than embracing its death, and it’s as nasty as it sounds. Among other things, when it kills someone, it has a chance to eat their soul to heal itself; if it succeeds, that person can’t be reanimated by anything less than a Wish or Miracle spell while the ravener remains “alive”. The Ravener also comes with a statblock for a sample version, a process for creating your own from an existing dragon, as well as the details for the ritual it takes to create one. Oh, and if a Ravener doesn’t consume enough souls, it “starves” and becomes a Ravener Husk – more of a mindless feral version of its former self — and there’s a statblock for that creature too. Needless to say, they couldn’t fit all of that on a single page.

Confession time. One of the first things I do when I get a book like this is to go looking for the most powerful creatures. I’m a sucker for that wow factor. Thanks to the index in the back (creatures arranged by level), the nastiest creatures check in at Level 23 – the Solar and the Jabberwock. Now… the Solar is actually a good guy (a member of the Angel family), but with a +44 holy greatsword and a list of INNATE spells that would put most Level 20 casters to shame, you probably don’t want to get on his bad side. The Jabberwock, on the other hand, is both a nasty dragon and an impressive literary nod, since it folds the Lewis Carroll poem “Jabberwocky” into the statblock at several points. Including, true to the Carroll poem, a special relationship with vorpal blades. Your party will probably hate fighting it… unless your party is comprised entirely of English majors, in which case… well, they’ll probably still die, but they’ll feel like they learned something in the process.

Confession time. One of the first things I do when I get a book like this is to go looking for the most powerful creatures. I’m a sucker for that wow factor. Thanks to the index in the back (creatures arranged by level), the nastiest creatures check in at Level 23 – the Solar and the Jabberwock. Now… the Solar is actually a good guy (a member of the Angel family), but with a +44 holy greatsword and a list of INNATE spells that would put most Level 20 casters to shame, you probably don’t want to get on his bad side. The Jabberwock, on the other hand, is both a nasty dragon and an impressive literary nod, since it folds the Lewis Carroll poem “Jabberwocky” into the statblock at several points. Including, true to the Carroll poem, a special relationship with vorpal blades. Your party will probably hate fighting it… unless your party is comprised entirely of English majors, in which case… well, they’ll probably still die, but they’ll feel like they learned something in the process. If you’re looking for RPG classics that didn’t make the cut the first time, we’ve got plenty of choices there as well. Everyone’s favorite stone-fed beef, the gorgon, is here. Remember the intellect devourer, the brain that walks around on stumpy little legs? He’s in here too, ready to hijack the nearest recently-deceased body. The froghemeth also puts in an appearance, because a giant frog wasn’t really complete until someone also gave it freaky tentacles. If you want to get crazy and take your campaign underwater, tritons and hippocampi are here for you.

If you’re looking for RPG classics that didn’t make the cut the first time, we’ve got plenty of choices there as well. Everyone’s favorite stone-fed beef, the gorgon, is here. Remember the intellect devourer, the brain that walks around on stumpy little legs? He’s in here too, ready to hijack the nearest recently-deceased body. The froghemeth also puts in an appearance, because a giant frog wasn’t really complete until someone also gave it freaky tentacles. If you want to get crazy and take your campaign underwater, tritons and hippocampi are here for you. What else is there to report? The artwork, as always, is top-notch. Focused on delivering the basic look of the creatures, so no big sweeping two-page panoramas, but works on a functional level. “You want to know what that creature looks like? Here you go!” Then again, if you’re old enough to have grown up in the Gygax days of this hobby, you remember when the first Monster Manual was basically slapping a cover on a bunch of monsters compiled from newsletters, which meant the art was hand-drawn sketches. The appendices are slim but functional – quick-references of creature abilities and traits, a few ritual spells related to creatures, a quick table of creatures by type, and then a full index of creatures, sorted by level.

What else is there to report? The artwork, as always, is top-notch. Focused on delivering the basic look of the creatures, so no big sweeping two-page panoramas, but works on a functional level. “You want to know what that creature looks like? Here you go!” Then again, if you’re old enough to have grown up in the Gygax days of this hobby, you remember when the first Monster Manual was basically slapping a cover on a bunch of monsters compiled from newsletters, which meant the art was hand-drawn sketches. The appendices are slim but functional – quick-references of creature abilities and traits, a few ritual spells related to creatures, a quick table of creatures by type, and then a full index of creatures, sorted by level.

With Alien Archive 3, it’s a bit more of a free-for-all, for better and for worse. This collection of creatures feels a little more improvisational and… weird. It doesn’t really have an overarching “theme” or anything like that. It’s not like “we’re gonna focus on this one Pact Worlds planet” or “we’re doing fire creatures this time; tell the printer to stock up on red and orange ink”. So… my internal grump feels like it’s a little haphazard and thrown together. On the other hand, it’s more fun and weird – they let their freak flag fly a little more on this one.

With Alien Archive 3, it’s a bit more of a free-for-all, for better and for worse. This collection of creatures feels a little more improvisational and… weird. It doesn’t really have an overarching “theme” or anything like that. It’s not like “we’re gonna focus on this one Pact Worlds planet” or “we’re doing fire creatures this time; tell the printer to stock up on red and orange ink”. So… my internal grump feels like it’s a little haphazard and thrown together. On the other hand, it’s more fun and weird – they let their freak flag fly a little more on this one. Believe it or not, it gets weirder. Someone decided to create the concept of the Weaponized Toy. The lore plays around with the idea of arms dealers disguising combat drones as toys to get them past Pact Worlds security, so… it’s basically killer jack-in-the-boxes or killer game systems. Also, there’s the kami – spirits that merge with objects and become anthropomorphic versions of that object. Think Transformers. There’s a diminutive version (the tsukumogami) which is a kind of cute nuisance and the gargantuan version (the chinjugami) which will wreck your day.

Believe it or not, it gets weirder. Someone decided to create the concept of the Weaponized Toy. The lore plays around with the idea of arms dealers disguising combat drones as toys to get them past Pact Worlds security, so… it’s basically killer jack-in-the-boxes or killer game systems. Also, there’s the kami – spirits that merge with objects and become anthropomorphic versions of that object. Think Transformers. There’s a diminutive version (the tsukumogami) which is a kind of cute nuisance and the gargantuan version (the chinjugami) which will wreck your day. The remaining appendixes are the “usual” stuff – creatures by CR, creatures by type, creatures by terrain. The one new entry here is a breakdown by Pact World planet, so if you’re planning an adventure on, say, Verces, you can immediately grab a list of some of the most common creatures on that planet.

The remaining appendixes are the “usual” stuff – creatures by CR, creatures by type, creatures by terrain. The one new entry here is a breakdown by Pact World planet, so if you’re planning an adventure on, say, Verces, you can immediately grab a list of some of the most common creatures on that planet.

It’s funny because part of me is writing this review under protest. There’s the book I knew Paizo would make, and frankly, the book they HAD to make. But there’s also the book I secretly hoped it would be, even though it was unrealistic.

It’s funny because part of me is writing this review under protest. There’s the book I knew Paizo would make, and frankly, the book they HAD to make. But there’s also the book I secretly hoped it would be, even though it was unrealistic. Starfinder was being built completely new from the ground up. They could afford to take risks and do things differently. With Pathfinder, they’re doing a refresh on an existing game system with a decade of inertia and an existing fanbase with prior expectations – most of the risk-taking is already baked into the core rulebook, so there’s something to be said for making the REST of the content familiar and reassuring. For making their Bestiary look like the six other Bestiaries they did for the original game. They don’t need to reinvent the wheel; they already reinvented the CAR, and the wheel just needs to fit on it.

Starfinder was being built completely new from the ground up. They could afford to take risks and do things differently. With Pathfinder, they’re doing a refresh on an existing game system with a decade of inertia and an existing fanbase with prior expectations – most of the risk-taking is already baked into the core rulebook, so there’s something to be said for making the REST of the content familiar and reassuring. For making their Bestiary look like the six other Bestiaries they did for the original game. They don’t need to reinvent the wheel; they already reinvented the CAR, and the wheel just needs to fit on it.

That’s not to say there’s NOTHING new in here. I kinda like the Nilith, which is basically a demonic tree sloth – except that it moves at normal speeds and has mind-affecting powers. Then there’s the Quelaunt, which looks like someone decided your average Area 51 Gray Alien needed an extra arm and leg, claws, and lack of facial features to be even more creepy. Its power-set revolves around fear powers. And claws. I think my personal favorite at first pass is the Skulltaker, which is an undead that one would describe as a sentient tornado of bones. As a neat flavor thing, it also can draw on the memories and experiences of all the bones that comprise it, so it has perfect Lore knowledge. Not a were-penguin, but cool stuff.

That’s not to say there’s NOTHING new in here. I kinda like the Nilith, which is basically a demonic tree sloth – except that it moves at normal speeds and has mind-affecting powers. Then there’s the Quelaunt, which looks like someone decided your average Area 51 Gray Alien needed an extra arm and leg, claws, and lack of facial features to be even more creepy. Its power-set revolves around fear powers. And claws. I think my personal favorite at first pass is the Skulltaker, which is an undead that one would describe as a sentient tornado of bones. As a neat flavor thing, it also can draw on the memories and experiences of all the bones that comprise it, so it has perfect Lore knowledge. Not a were-penguin, but cool stuff. Some pages have sidebars with additional content, but the content of those sidebars is a mixed bag. Sometimes it’s very rubber-meets-the-road stuff like a creature’s spell list or how to manage a particular power as GM. Other times – particularly with the humanoid races – I’ll give it credit for approaching the world-building that I liked in the Alien Archive. There are times where it’s precariously close to filler text – there was some blurb that mentioned that a particular creature (one of the giants, I think) might have exotic treasure. I SHOULD HOPE SO.

Some pages have sidebars with additional content, but the content of those sidebars is a mixed bag. Sometimes it’s very rubber-meets-the-road stuff like a creature’s spell list or how to manage a particular power as GM. Other times – particularly with the humanoid races – I’ll give it credit for approaching the world-building that I liked in the Alien Archive. There are times where it’s precariously close to filler text – there was some blurb that mentioned that a particular creature (one of the giants, I think) might have exotic treasure. I SHOULD HOPE SO.