Make sure to check out the Battlezoo Bestiary! Over 100 new monsters, the new Monster Parts System, play as a Dragon, the level 1-11 Jewel of the Indigo Isles Adventure Path, and more! Check it out now!

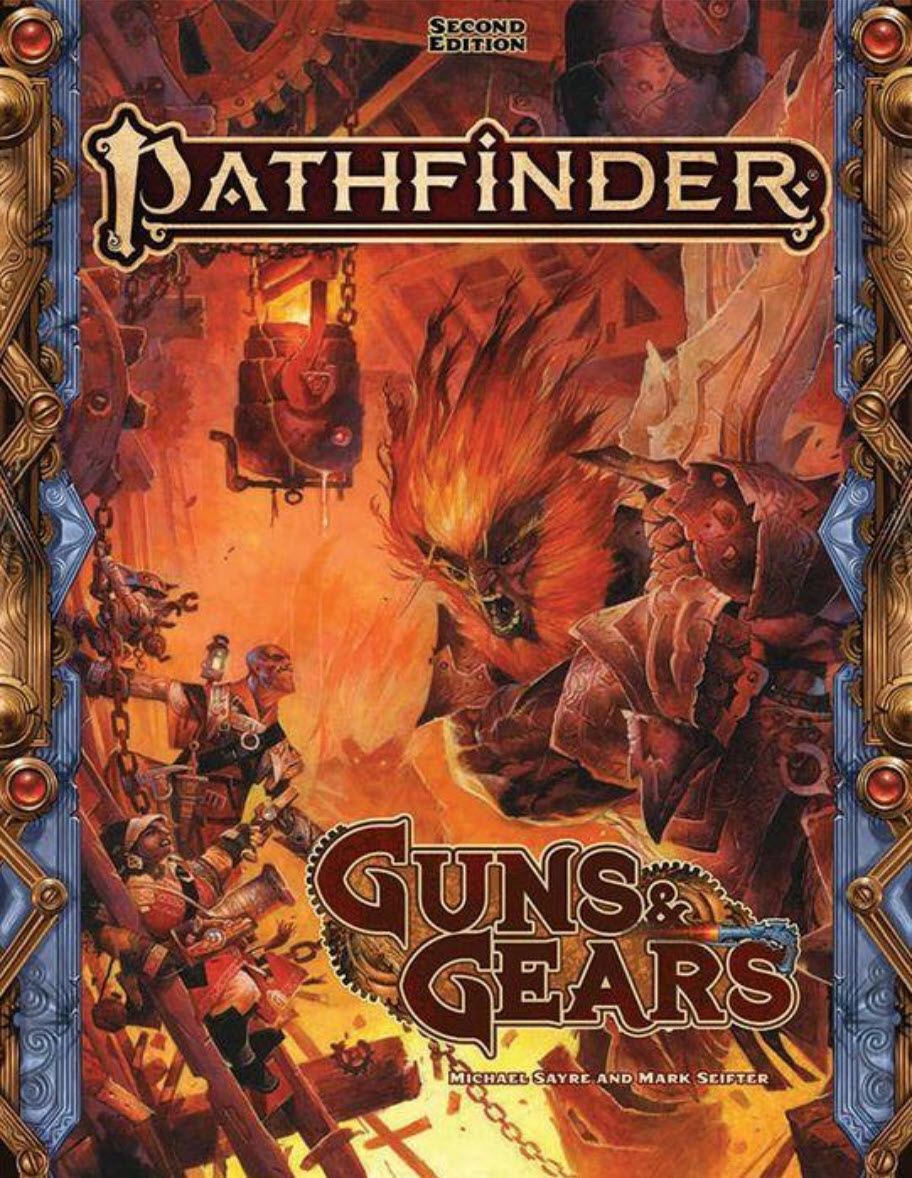

It was just a month or so ago, Paizo invited us to dive into magical wonders with Secrets Of Magic, arguably my favorite Second Edition hardcover so far. This month, they’re right back at it with an equally satisfying exploration of Golarion’s technological marvels, with the release of Guns & Gears. It’s not QUITE as epic an undertaking… maybe because magic is everywhere while technology is still a bit more of a niche thing… but it’s still a solid book that adds a lot of new content to the Second Edition world (some of which will be familiar to First Edition ex-pats).

First and foremost, Guns & Gears adds two new classes – the Gunslinger and Inventor. There’s a new ancestry: automatons. There are lots of backgrounds and archetypes to add a little tech flavor to all the pre-existing character options. And of course the gear… OH, SO MUCH GEAR.

Now I have to admit something going in. Are you old enough to remember those commercials for Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups where someone would actually get offended that someone “got chocolate in my peanut butter” and the other person got offended that the first person “got peanut butter in my chocolate” (and then they’d both pull their heads out of their asses and realize “peanut butter + chocolate” is a fundamental building block of civilized society)? For a LONG time, that’s how I was with technology in my swords-and-sorcery roleplaying games. Younger Me was an RPG Luddite at heart. In fact, I once played a hunter in World of Warcraft where I literally sold off every firearm I came across because bows were the weapon of a TRUE hunter. AT NO POINT IN THE TRILOGY DID LEGOLAS “PACK HEAT”.

If I can try to intellectualize an ultimately emotional decision, I think it was some sort of mental corollary to Clarke’s Third Law. “The more you can do with technology, the less magic seems exotic and otherworldly, so if you allow a bunch of devices that do all the stuff spells can do, what’s the point of magic?” But the point of all of this is that’s a pre-existing bias I’ve had to get past over the years, and at least in First Edition, I regarded the Gunslinger with more than a little skepticism.

But reading through Guns And Gears, I may be changing my tune, and not just because playing a leshy gunslinger whose nickname is “The Salad Shooter” would be Dad-Joke hilarious. In fact, the Gunslinger and Inventor look like they might both be worth kicking the tires on.

Before I start digging in, I wanted to comment a little bit on the layout of this book, as Paizo went in a slightly different direction this time around. Previous Paizo releases have followed the same basic layout of the Core Rulebook, keeping to the Ancestry-Background-Class flow. This time, Paizo decided to break things up into three mini-books: there’s a “Gears” section, a “Guns” section, and then a smaller part at the end that delves into the lore and other “softer” content. In fact, my little birds tell me that “Guns” and “Gears” started out as separate projects entirely, before being merged into one volume, which… yeah, that kind of explains things.

I’m still trying to decide how I feel about this, though. You can make a case either way. On one hand, it keeps all the content for a particular class together. If you’re building an Inventor, you don’t have to go sifting through a bunch of guns content and vice versa. On the other hand, it’s a little weird to have to go looking for the gunslinger class info out in the middle of the book, rather than up front where you’d usually expect it to be. I suppose it’s something I’ll get used to, but it’s a little weird the first few times. And in either case, when you’re talking about using it in the context of online tools, it’s ALL just a search box or a drop-down away, however, Paizo chose to organize the hardcover.

(Also, if one really gets nit-picky, if you’re going to put Gears first, shouldn’t it be Gears & Guns? OK… I’ll shut up now.)

But let’s get to the content, and we lead off with the Inventor. The Inventor is a technologist who creates and manipulates mechanical devices. It’s a class that’s brand-new in Second Edition, but I got a twinge of familiarity while reading it because it clearly draws some inspiration from the Mechanic class in Starfinder. So much so that I’ve already contemplated building a Pathfinder version of Tuttle Blacktail and CHDRR. As with other classes that have different paths, an Inventor character differentiates themselves through the creation of a signature item, their “innovation”, which can be either a custom weapon, a suit of armor, or a construct minion. But let’s be honest: the Rule of Cool STRONGLY argues in favor of the construct path – having your own little RoboBuddy to command is pretty awesome. I speak from (sci-fi) experience on this one.

Along with the usual progression through feats, you periodically receive new augmentations to your innovation, making it more powerful as you level. Just to pick one example, your construct can go into turret mode where it is immobilized, but has a greater range on attacks and does more damage. Meanwhile, your weapon might be able to switch between ranged and melee configurations. Oh, and like any good technologist, you can rig your creation to explode if you really get in a tight spot.

Even though it’s jumping ahead in the book, I’m going to finish up with classes and discuss the Gunslinger. It’s exactly what it sounds like – a character who specializes in firearms (which includes crossbows). Now, unlike the Inventor, there WAS a Gunslinger class in First Edition, but this version’s been reworked and simplified a little. The First Edition Gunslinger operated on points (“grit”) that you could generate through actions and then spend on special abilities, much like the Swashbuckler operates on “panache”. However, the 2E Gunslinger is a little more straightforward, doing away with grit, and just relying on class feats and special abilities, known as “deeds”. One thing I did not expect: Gunslingers are given medium armor proficiency, and some of their builds incorporate melee and are expected to be right in the thick of combat.

As with the Inventor, there are multiple paths a Gunslinger can choose. The Way of the Drifter is a build that focuses equally on guns and melee weapons (think “pirates” running around with a cutlass and pistol). The Way of the Pistolero is a “fast feet, faster talker” build that focuses on movement abilities and personal-interaction effects that confuse and demoralize opponents. The Way of the Sniper is, well, a sniper: you sacrifice speed in favor of packing as much damage as possible into each shot and also get some stealth benefits. And there’s also a heavy build – The Way of the Vanguard – that’s more in-your-face: blasting people with shotguns, using your gun as a melee weapon to smash people, and such. It will probably not come as much of a surprise to learn that dwarves invented this style of fighting. So for a class that sounded like it would run the danger of being one-note, it seems like there are a lot of different feels you can aim for.

“Aim for”. For a gunslinger. Get it? Get it? IT’S GOLD, JERRY!

We also have a new ancestry, the automaton. Whereas the Android from the Lost Omens Ancestry Guide is a fusion of organic and technology, Automatons are pure tech, living constructs. Think of it as the difference between Data vs. C3P0. I should warn you that this is one of those cases where Paizo goes against their usual love of keywords: although they are technically “constructs”, they don’t have the typical immunities that come with the “construct” keyword and can also be healed by positive energy. So they’re constructs in concept but hew closer to organic beings in terms of touchpoints with the rules. They don’t need to eat or drink, but sleeping (a “rest state”) and breathing (“venting magic-infused gas”) both have equivalent processes that amount to the same thing. I assume it’s ease-of-use: an ancestry where everything works JUST a little differently isn’t going to be very popular with GMs; an ancestry where they’re basically organics except for one or two exceptions is far easier to administer.

The thing that strikes me at first glance about Automatons is their customizability. There are four basic builds: hunter, mage, sharpshooter, and warrior that help define your starting abilities. And it’s true that SOME of the ancestry feats are tied to a specific build (the hunter can get a camouflage that’s only available to them, for instance). But a LOT of the ancestry feats are available to any automaton build. So if you want to be a mage build, but with the Reinforced Chassis that gives you a bonus to AC, that’s just fine. And speaking of that Reinforced Chassis, it chains into a reaction ability (Chassis Deflection) where you can attempt a DC 17 check to turn a critical hit into a regular hit if it’s against physical damage. (20 percent chance to negate a crit? YES PLEASE.)

As you would expect, both the Guns and Gears sections of the books also present backgrounds and archetypes you can use to add a sprinkle of technological flavor to your more conventional characters. The backgrounds come in both common and uncommon varieties, with the common ones applying your usual ability scores, skills, and lore, while the uncommon ones are a little more exotic in their effects (and generally require GM approval to use).

One of my favorites – from the Gears side – was the Discarded Duplicate. You’re a being who was created as a spare copy of someone else. So as you go out into the world, you may run into and interact with the life of the “original” version of yourself. Maybe Other You is a famed politician… or maybe they’re a serial killer. But whoever they are, they’re enough of a high-roller that they had the resources to commission a clone at some point, right? That’s a roleplaying goldmine right there. On the Guns side of the house, I liked the Revenant, a very Clint Eastwood-ian entity that was killed but decided not to stay dead because they still had scores to settle. Not undead, but also not 100% alive either, which manifests in negative healing – responding “backward” to positive and negative energy, as undead do. Also, if you make a Revenant Barbarian, you’re a stone’s throw from building the Undertaker from WWE. All you need is the hat and the eyeliner.

There are equally interesting options for archetypes. The most interesting one here is the Spellshot, which is a full-class archetype for the Gunslinger, fusing magic and guns to create interesting effects like re-summoning ammunition from shots that miss. If you think about it, it’s analogous to the Eldritch Archer for bows. I also liked the Gears archetype “Sterling Dynamo” which is “hey, what if my character just had a robot arm?” Not as a static background (which you can also do), but as a piece of tech that grows and adapts along with you. Another interesting one is the Firework Technician which is a Guns archetype that’s like a highly-specialized alchemist. You make things go boom, but with interesting effects that distract or draw attention. No word on whether you can make a flag that says “BANG!” come out of your opponent’s gun barrel, and THEN explode.

Of course, both sub-books also have tons of new gear, but the Gears side is naturally going to get the lion’s share of that, and the variety is what stuck out to me. Of course, they’re going to have some tech that duplicates the function of magic items, but they also have gadgets – single-use items that fill a similar role to consumables. There’s a selection of tech-based traps and hazards. They have vehicles and siege engines if you want to take your campaign to a more macro level. (And with one of the vehicles being a giant mechanical octopus, you’ll probably want to.) They also have both mundane and exotic wheelchairs, because there’s been a sense in the community that players with disabilities still ought to be able to see themselves as heroes and play heroic versions of themselves as well. (My only complaint about this is that the “Spider Chair” causes unfortunate flashbacks to the dreadful Wild Wild West movie, but that shouldn’t negate the principle of positive representation.)

The tech on the guns side is, by definition, a little more narrow in scope. No great surprise… it’s all gun-based. So you have a wide variety of firearms, the most exotic of which are “beast guns”, which are a fusion of magic and creature parts. So if you want a gun made from a dragon’s trachea that shoots the dragon’s former breath weapon attack, or if you want a gun that shoots squid tentacles to entangle people, Paizo’s got you covered. The support tech is mostly stuff that makes guns work better – scopes, reloaders, stabilizers, etc. The siege weapons are artillery pieces – cannons, mortars, and the like. Not nearly as exotic as the Gears side, but that’s kinda how it goes.

The third mini-book of the collection is “The Rotating Gear”. This is the lore section of the book – part history lesson, part campaign setting, part idea incubator for roll-your-own GMs. Now, if you’re just a group that plays published adventure paths, you may miss most of this or get a paragraph or two of it in handout form and move on. On the other hand, if you’re building your own campaigns, or if you’re just really into the lore of the Pathfinder world, this section is where the worldbuilding happens. If you need a place to set your campaign where technology flourishes, or an NPC who would have a tech connection, this is the section of the book you’re going to lean most heavily on.

So that’s Guns and Gears. Let’s just accept that I’m going to probably whine a little bit about technology in my swords-and-sorcery game. It’s my one “get off my lawn” concession to my age and Gygax-Tolkien roots. But at least in the Second Edition world, technology is here to stay, and Guns and Gears adds a lot of good stuff to that side of the house for the people who are into it. If you’re fired up to include those elements in your game, steampowered-jetpack or giant-mechanical-octopus your way to your local gaming store and pick this one up.

The first is giving some love to the Tian Xia region. There’s a LOT of material in this book that’s either EXPLICITLY tied to the Tian Xia region, or at least bears east Asian influences and flavor in its design. All of the dragons are explicitly of Tian Xia, as is a multi-page entry on kami, divine nature spirits that guard places of importance. But you also see it in something like the terra-cotta warrior – not explicitly defined as being of Tian Xia (by definition, it’s “just” a stone soldier), but certainly bears the influences design-wise. Or the locathah… a humanoid that bears the visual stylings of a lionfish, which are indigenous to the Indo-Pacific in real life.

The first is giving some love to the Tian Xia region. There’s a LOT of material in this book that’s either EXPLICITLY tied to the Tian Xia region, or at least bears east Asian influences and flavor in its design. All of the dragons are explicitly of Tian Xia, as is a multi-page entry on kami, divine nature spirits that guard places of importance. But you also see it in something like the terra-cotta warrior – not explicitly defined as being of Tian Xia (by definition, it’s “just” a stone soldier), but certainly bears the influences design-wise. Or the locathah… a humanoid that bears the visual stylings of a lionfish, which are indigenous to the Indo-Pacific in real life.

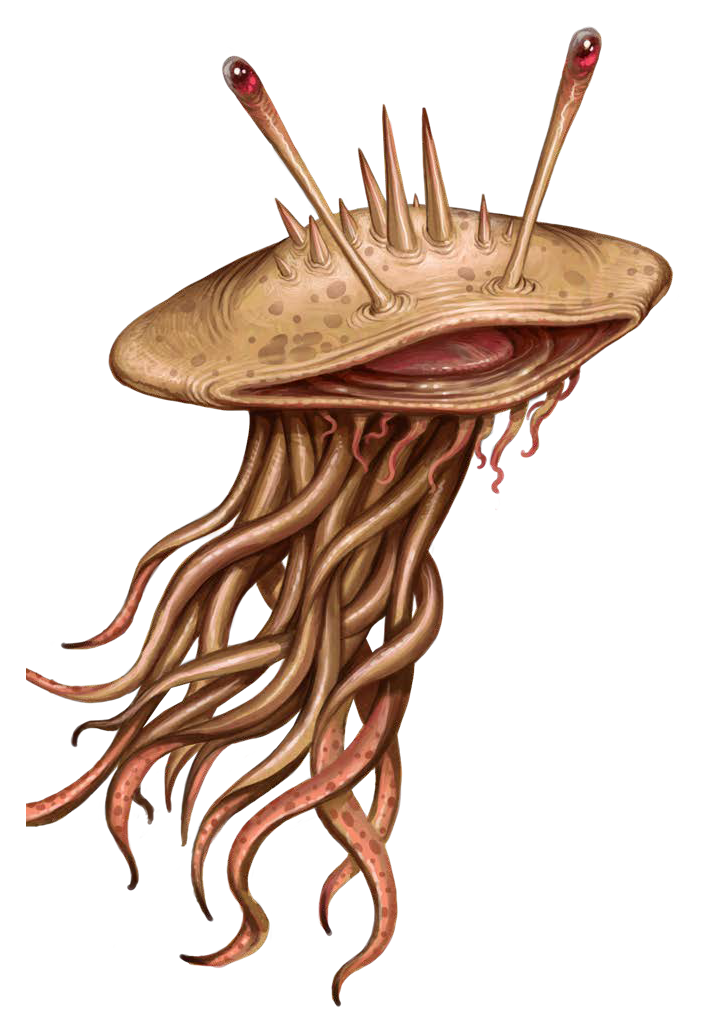

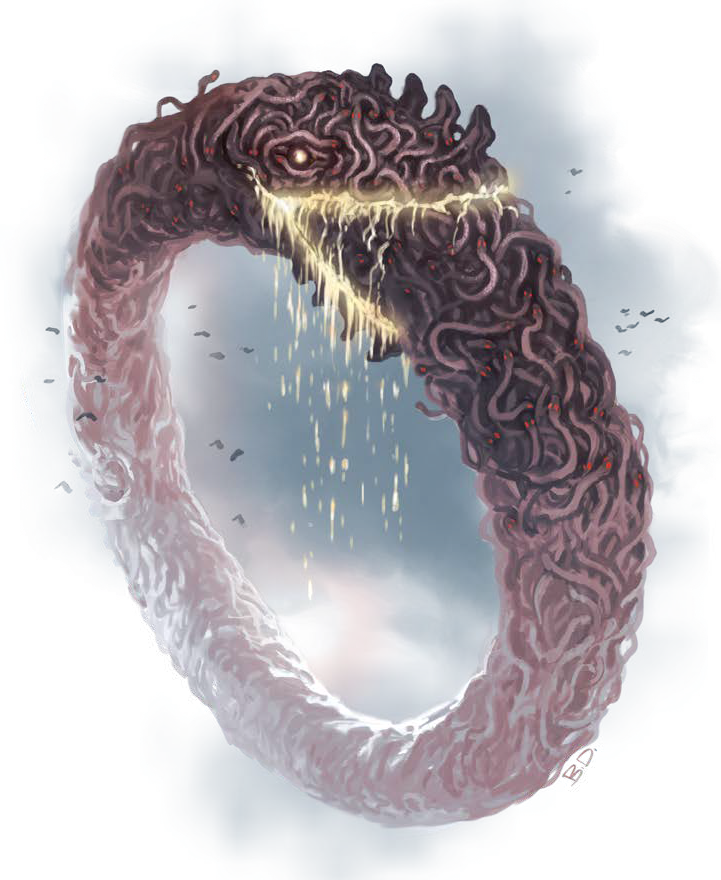

Now, I could probably name another 20 monsters and you’d like some of them and maybe have others you think I should’ve put higher on my list, but I think that gets you an idea of the feel of this book. It’s a little more exotic than the other two Bestiaries, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Familiarity is comfortable, but familiarity also runs the risk of becoming routine. Why settle for another 20 fights against orcs when you can tussle with something you’ve never seen before?

Now, I could probably name another 20 monsters and you’d like some of them and maybe have others you think I should’ve put higher on my list, but I think that gets you an idea of the feel of this book. It’s a little more exotic than the other two Bestiaries, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Familiarity is comfortable, but familiarity also runs the risk of becoming routine. Why settle for another 20 fights against orcs when you can tussle with something you’ve never seen before?